Thoughts on Tane Wo Maku Tori

I recently became the proud owner of a WonderSwan Color, Bandai’s would-be rival to the Game Boy. The two systems famously share the same lead designer, Gunpei Yokoi, who brought his hardware design philosophy forward with several outright improvements over the Game Boy alongside a few interesting twists. Most notably the console’s twin d-pads oddly stacked on top of each other, giving you the ability to play games in both landscape and portrait orientation. The console’s slim library may seem overloaded with licensed garbage impenetrable to anyone who can’t read Japanese, but the WonderSwan was also home to more than a few interesting experiments that give the system a unique character and appeal. Whether that be the remote controlled WonderBorg accessory, a commercially released devkit called WonderWitch, or the game we’re looking at today: Tane Wo Maku Tori.

Tane Wo Maku Tori, which we can translate as Seed Sowing Bird, was the end result of a competition held on the gameshow D’s Garage 21. Viewers were asked to send in their own game design documents which would be pitched to various publishers, the winner being Tsunehisa Suzuki, who came up with a unique action-puzzler based on Amidakuji, a traditional lottery method used in Japan. Amidakuji consists of a grid of vertical lines with individual players being assigned a space at the top of each line, and the items that they’re drawing for given a space at the bottom. Horizontal lines are then randomly drawn connecting each column, and players then draw a path from top to bottom with the stipulation that every time a horizontal line is reached, they travel across it before resuming their descent.

Tane Wo Maku Tori, which we can translate as Seed Sowing Bird, was the end result of a competition held on the gameshow D’s Garage 21. Viewers were asked to send in their own game design documents which would be pitched to various publishers, the winner being Tsunehisa Suzuki, who came up with a unique action-puzzler based on Amidakuji, a traditional lottery method used in Japan. Amidakuji consists of a grid of vertical lines with individual players being assigned a space at the top of each line, and the items that they’re drawing for given a space at the bottom. Horizontal lines are then randomly drawn connecting each column, and players then draw a path from top to bottom with the stipulation that every time a horizontal line is reached, they travel across it before resuming their descent.

The concept has a lot of clear game design utility, so unsurprisingly it’s reared its head in plenty of video games. From small sequences like the Bospider fight in Mega Man X, to the entire skeletons of games like Konami’s 1982 arcade title Amidar and the Japan-only Game Boy puzzler Soreyuke‼ Amida-kun. So it’s slightly disappointing that our contest-winning game here cribs so heavily from such a well trodden concept, but Tane Wo Maku Tori is able to put any doubts to rest by virtue of being a unique take on the concept with pitch-perfect execution.

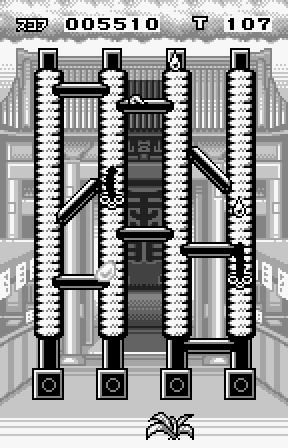

Each level begins with our titular bird titularly sowing their titular seeds at random endpoints of the grid. Water droplets then continuously pour down from the top, and it’s your job to guide them to each seed, watering each one to a full bloom. The only way you can manipulate the playfield is by shifting the horizontal lines of each column up or down. So while the individual droplets are quite small and slow, through smart manipulation of the grid you can combine them up to three times, causing them to move slightly faster each time. There’s a bit of a learning curve here, but an equal amount of nuance too. For instance, if two droplets are on the same row and travelling in the same direction, you can close the distance between them by waiting until the first one reaches the next column over, then shifting the row down a step. This will cause that drop to re-enter the row, now travelling in the opposite direction where it will collide with the other droplet. Similarly, if one is travelling straight downwards, you can prevent it from taking a turn by shifting the row at the last second. These are the details that lend Tane Wo Maku Tori a distinct action game flavor, where quick reflexes are just as important as long-term strategic thinking.

Each level begins with our titular bird titularly sowing their titular seeds at random endpoints of the grid. Water droplets then continuously pour down from the top, and it’s your job to guide them to each seed, watering each one to a full bloom. The only way you can manipulate the playfield is by shifting the horizontal lines of each column up or down. So while the individual droplets are quite small and slow, through smart manipulation of the grid you can combine them up to three times, causing them to move slightly faster each time. There’s a bit of a learning curve here, but an equal amount of nuance too. For instance, if two droplets are on the same row and travelling in the same direction, you can close the distance between them by waiting until the first one reaches the next column over, then shifting the row down a step. This will cause that drop to re-enter the row, now travelling in the opposite direction where it will collide with the other droplet. Similarly, if one is travelling straight downwards, you can prevent it from taking a turn by shifting the row at the last second. These are the details that lend Tane Wo Maku Tori a distinct action game flavor, where quick reflexes are just as important as long-term strategic thinking.

Complicating matters are the swarms of bugs which patrol the field, also adhering to the rules of Amidakuji. They’ll drink up any droplet and munch on any flower they come into contact with, the latter causing a game over. You can slow them down by leading them towards a dead end, where they’ll pause for a moment before making their way back up the full length of the playfield. More importantly, you can take them off the field entirely by hitting them with a third-stage droplet, indicated by a flashing sprite. You can combo multiple bugs with the same drop, then finish by leading it to a flower for massive points. Watering a flower this way is worth a base value of 100 points, but is multiplied by the number of droplets you collect along the way. Droplets speed up considerably after touching a bug, so a lengthy chain like this can take either a remarkable amount of planning, quick reflexes, or pure luck to pull off. Sometimes all three.

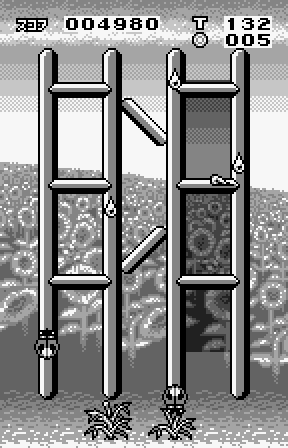

Luck in general seems to dominate Tane Wo Maku Tori, it’s easy to write-off the game prematurely since failure can feel entirely random. Once a bug has reached a seed, the game gives you about 5 seconds to kill it before it’s game over. But even with such a generous lead time, recovery can be difficult to impossible if you don’t have any third-stage droplets already on screen. It’s worth noting that you can speed up the droplets at any time by holding the x3 button, but even then there’s sometimes nothing to do but wait for the game to fail you. This is surely a large part of why the game has a mixed reception, it’s extremely discouraging to new players. But no matter how chaotic the game can be — maxing out with five bugs onscreen and three flowers to water — each game element behaves based on simple, clearly defined rules. Failure is not random, it’s only a delayed punishment for mistakes made earlier in the game.

Luck in general seems to dominate Tane Wo Maku Tori, it’s easy to write-off the game prematurely since failure can feel entirely random. Once a bug has reached a seed, the game gives you about 5 seconds to kill it before it’s game over. But even with such a generous lead time, recovery can be difficult to impossible if you don’t have any third-stage droplets already on screen. It’s worth noting that you can speed up the droplets at any time by holding the x3 button, but even then there’s sometimes nothing to do but wait for the game to fail you. This is surely a large part of why the game has a mixed reception, it’s extremely discouraging to new players. But no matter how chaotic the game can be — maxing out with five bugs onscreen and three flowers to water — each game element behaves based on simple, clearly defined rules. Failure is not random, it’s only a delayed punishment for mistakes made earlier in the game.

Like many great maze action games, Tane Wo Maku Tori is best played with a sort of detached thousand-yard stare. Not focusing on anything in particular, but instead the totality of the playfield and the paths that each game element will take. A decent general strategy is to try to keep bugs towards the center of the grid, not too high that they’ll drink up all the water, and not too low that they’ll eat your flowers. Similarly, you’ll always want to keep at least one third-stage droplet around in case anything goes awry. This can prove especially difficult, since if they take on any more water they’ll grow too heavy and immediately fall off the playfield (though they’ll still take out any bugs they hit along the way and net you 1000 points!).

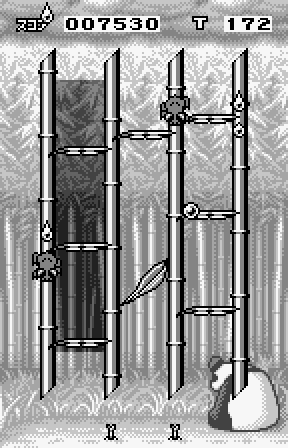

The story mode’s eight levels may sharply ramp up in difficulty, but with practice the chaos shifts from overwhelming to understimulating. Unsurprisingly then, you’re going to get the most longevity out of the game via its endless mode which features three difficulties that are progressively unlocked each time you bloom 10 flowers. The max difficulty starts out with three bugs and three flowers, as well as a sloped line in every column; these serve as one-way platforms for your droplets, but can be traversed by bugs in either direction. This complicates your pathfinding process significantly, and combined with a tighter time limit creates a hell of a challenge. One where the central conflict between clearing bugs to create space and growing flowers to gain time comes into the sharpest focus.

The story mode’s eight levels may sharply ramp up in difficulty, but with practice the chaos shifts from overwhelming to understimulating. Unsurprisingly then, you’re going to get the most longevity out of the game via its endless mode which features three difficulties that are progressively unlocked each time you bloom 10 flowers. The max difficulty starts out with three bugs and three flowers, as well as a sloped line in every column; these serve as one-way platforms for your droplets, but can be traversed by bugs in either direction. This complicates your pathfinding process significantly, and combined with a tighter time limit creates a hell of a challenge. One where the central conflict between clearing bugs to create space and growing flowers to gain time comes into the sharpest focus.

Further elevating the game is the adorable illustration work from artist Shoko Toda which does a tremendous job conveying the abstract mechanics intuitively. Alongside the usual instruction manual, the game was also packaged with a wonderfully printed children’s book-style collection of cutscene art, where a lonely crow covers the land in flowers so that their migrating friend will come back and play. It’s these flourishes that turn what could have been an otherwise unassuming puzzle game into one of the standout WonderSwan titles.

What you’re looking at right now is every possible game state within Game & Watch: Octopus contained in a single image file. Looking at it is a weirdly surreal experience for me. I spend an unhealthy amount of my time thinking about and writing about games; going on and on about “depth” and “possibility spaces” or whatever it is I do. The struggle in writing about these things though is that as much as I want to speak in absolute terms, these are not concepts that can be easily measured, if they can be measured at all. Like what is the total number of non-redundant game states possible within God Hand? Who the hell knows? Defining the depth of a game mostly comes down to a relative gut feeling. Not here though. A single image is all we need to visualize every possible combination of game states.

What you’re looking at right now is every possible game state within Game & Watch: Octopus contained in a single image file. Looking at it is a weirdly surreal experience for me. I spend an unhealthy amount of my time thinking about and writing about games; going on and on about “depth” and “possibility spaces” or whatever it is I do. The struggle in writing about these things though is that as much as I want to speak in absolute terms, these are not concepts that can be easily measured, if they can be measured at all. Like what is the total number of non-redundant game states possible within God Hand? Who the hell knows? Defining the depth of a game mostly comes down to a relative gut feeling. Not here though. A single image is all we need to visualize every possible combination of game states.